Athens Syndrome

Ashley Denny Petch

What is the opposite of Paris Syndrome? I think I have it. Athens cannot disappoint me, as hard as it may try. The hot garbage. The constant yelling. The oppressive concrete. Yes please. Sign me up. Inundate me.

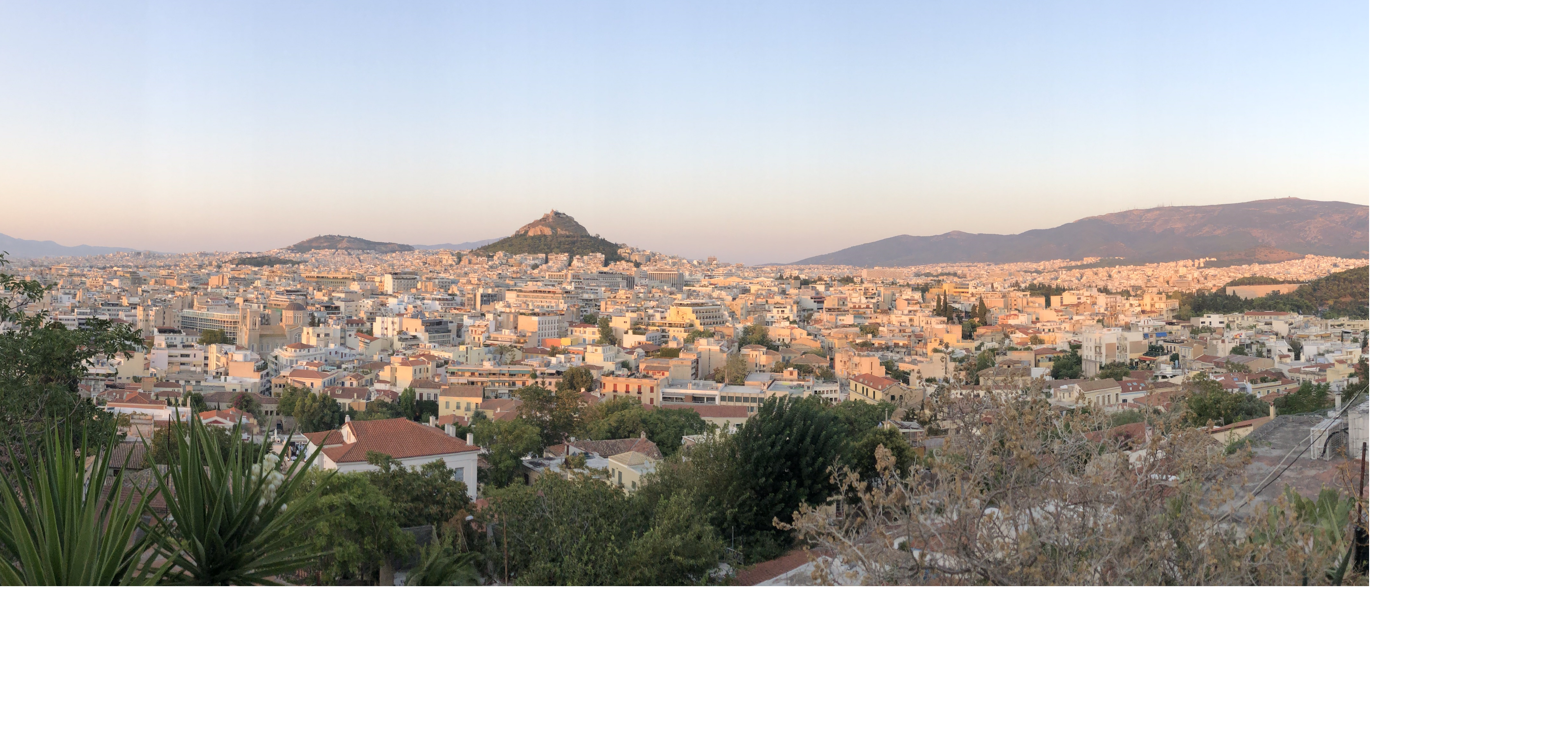

“Don’t romanticise them!” is the warning I received (and have failed to heed) when I told my Greek friends that I wanted to write about the polykatoikias that consume the congested Athens skyline. They are a housing style, anarchic and utilitarian, unique to Greek cities. They were built by civil engineers, not architects. They’re a neo-classicists’ nightmare. But when that pink, crepuscular, Athens light hits them at the right angle, well to me, they’re as beautiful as the Parthenon.

Polykatoikias (pol-ee-kat-ee-KEE-ahs) are purpose-built, concrete apartments with tiered, wrap-around balconies. Based on Le Corbusier’s concept of the Dom-ino House, they typically consist of 4 - 7 levels of flat concrete frames filled with brick, with concrete pillars replacing the need for load-bearing interior walls. Mostly undecorated and in a grey-ish wash, they were constructed to make the most out of the available space. They are all function, very little form; the endless purple spiderwort and olive trees pouring out from the balconies being the ornamental exception to this rule.

In the aggressive absence of any aesthetic, polykatoikia have become an aesthetic unto themselves. And, they helped solve a very acute problem for Greek society, starting in the 1950s all the way into the 80s.

History time! By the 19th century, Athens had become a small and insignificant village, where sheep grazed the fields surrounding the ramshackle ruins of the Acropolis, its glory very much in the past.

When modern Greece officially became a country in 1833, the Peloponnesian port town of Nafplio was initially selected as the capital. The British Empire, never missing an opportunity to stick one of their seemingly endless fingers into a new pie, heavily supported Greek revolutionaries with financial and military support during the war against the Ottomans. Driven by their romanticised admiration for ancient Greece, the Brits demanded that Athens become the capital instead. They sent a team of architects to redesign the city in this classical image. Stately neoclassical structures were erected to replace and erase the architectural remnants of the intervening four centuries of Ottoman rule, thereby promoting a fabricated but potent narrative of an uninterrupted lineage of the Greek "race".

This new capital of this new nation state faced successive crises in the 20th century, among them population exchanges with Turkey (1923), Nazi occupation during WWII (1941 - 1944), a bloody civil war (1946 - 1949) and subsequent military junta (1967 - 1974). All told, this meant that by the mid-century onwards, the population of this once-forgotten backwater surged with refugees and new residents. The need for housing was urgent.

Enter polykatoikias.

They were constructed with almost no state intervention, and built on the concept of antiparochi, in which developers buying the land gave the landowners a share (usually 2 or 3 flats) of the constructed units once completed. They were built rapidly and cheaply, and bolstered the economy by employing builders and workmen throughout the city. Neo-classicist no more, by the 1980s, Athens was enveloped in these concrete monsters that would have made Lord Byron weep uncontrollably at the sight of them.

They weren’t entirely residential either. Zoning was only practised for heavy industry in Athens, which led to many shops, cafes, medical offices, workshops being built into the ground floor of many a polykatoikia. Athens is an accidental masterclass in the 15-minute city.

As with any degree of communal living, problems arise. Polykatoikias employ a system of central heating, which, in a country facing a never ending energy crisis, means that more often than not, this central heating system is never turned on. In the winter, keeping the lights on and the flat warm are serious problems for most residents that the Greek state has no interest in solving.

Polikatoikias are often described as “modernist tenements''; they are local and vulgar. They encapsulate what makes Athens such an interesting place. The sheer proximity of everyone and everything is at once suffocating and thrilling.

Here comes more romance: I have had the pleasure to live in two polykatoikias so far in my lifetime. One in Koukaki, in the centre of Athens, a 5 minute walk from the Acropolis; the other in Galatsi, a dense suburb to the north of the city centre.

Both of them had giant balconies. The balcony is an essential element of a polykatoikia’s essence. You can let your whole life spill out onto these balconies.

An incomplete list of sights, sounds and smells experienced from the balcony of a polykatoikia:

- Mothers yelling at their children

- Wives yelling at their husbands

- Husbands yelling at their children and wives

- Dogs barking

- Babies crying

- Someone’s pet turtle contemplating ending it all

- Tourists partying very late into the night, and then an angry Greek woman telling them to shut the hell up, in Greek first and then English

- The smell of excessive barbecue on Tsiknopempti (Fat Thursday)

- Trumpet practice

- Cigarette smoke

- Roving night musicians singing Greek folk songs - strumming their bouzoukia and tambourines across the neighbourhood, stopping at each cafe to perform

- Rolling blackouts in the summer heat, followed by dogs barking and babies crying

- A store alarm going off on every Sunday at 9am without fail

- The baristas at the coffee shop below fighting with reckless drivers on the street

The DIY spirit in which polykatoikias were built reflects the city back onto itself. Athens is beautiful and chaotic and a mess; Athens is a mess because Greece is a mess. Greece started out as a protectorate and never really stopped being one. Time and time again, Greeks have been violently disabused of the notion that those in power (at all levels of governments) care about their welfare.

After the dictatorship, successive conservative governments have relied upon, and enforced the myth of a ‘Greek’ race. The state’s refusal to recognize ethnic plurality has resulted in the kind of terror and violence that modern nation-states excel in.

My favourite neighbourhood in Athens is Kypseli. Kypseli means ‘beehive’, and it’s a perfect descriptor. Kypseli is a slight valley, and when I walked from my Galatsi suburb into the city centre, I could feel the earth dipping as I arrived into this beehive. It’s one of the densest areas in all of Europe. It has a wonderful linear park called Fokionos Negri lined with cafes, shops and markets overlaid by, you guessed it, polykatoikias. It’s the most diverse area of Athens, by a long shot. The anarchist bookstore is run by a Frenchman. An Icelander owns a delightfully weird musical instrument emporium. We had falafels at the Syrian restaurant the night I got married. While socially segregated, here you see many Nigerian faces. East-Indian faces. You see hijabs. Kypseli has nothing to do with the myth of Ancient Athens. Athens has nothing to do with Ancient Athens.

The commotion is part of what makes Athens so alluring. It invites you to forget yourself. Athens reminds me that I’m alive. I’m sentimentalising again, I know. An Athenian would laugh at me, and rightly tell me that I would go crazy if I had to live in this powder keg metropolis. That it’s only romantic because I can opt-in to the chaos whenever I choose. That the suffocating heat, the dogs barking, the ambient tension ever present in the city would eventually engulf me.

So, I suppose what I’m saying is that I wish to be engulfed. Becoming Concrete. Being made Concrete. We are the Concrete Borg. Resistance is futile.

Further reading:

Why does Athens look so quirky?

Behind the Accidentally Resilient Design of Athens Apartments Spatial proximity and social distances: vertical social differentiation in an appartment block of Athens